Enshittification. Elected as the word of 2023, it describes the process of gradual decline in the quality of a product or service. A trend that has been growing. What does the process of enshittification look like? How does it start? And why should you care to avoid or reverse this trend?

Enshittification: the slow decay of online products and how to avoid it

The 3 phases of enshittification

1. The ‘lock-in’

Enshittification occurs in phases. Phase 1 is known as the ‘lock-in’ phase. A new product often sprouts from an unaddressed problem or a new technology. The company tries to lure as many new users as possible, so they spend time on the user experience. Common examples are Facebook, Uber, Netflix, Adobe… The product is actually trying to solve the problem for the user, and they don’t have to pay a lot yet, so they become more dependent. So far, so good, right?

At some point, it becomes harder for the product to acquire new users and grow their user base. An executive looks at the numbers, thinks really hard, and puts the following suggestion forward: “Let’s focus on the monetization per user.” Phase 2 kicks into action.

2. Monetization per user

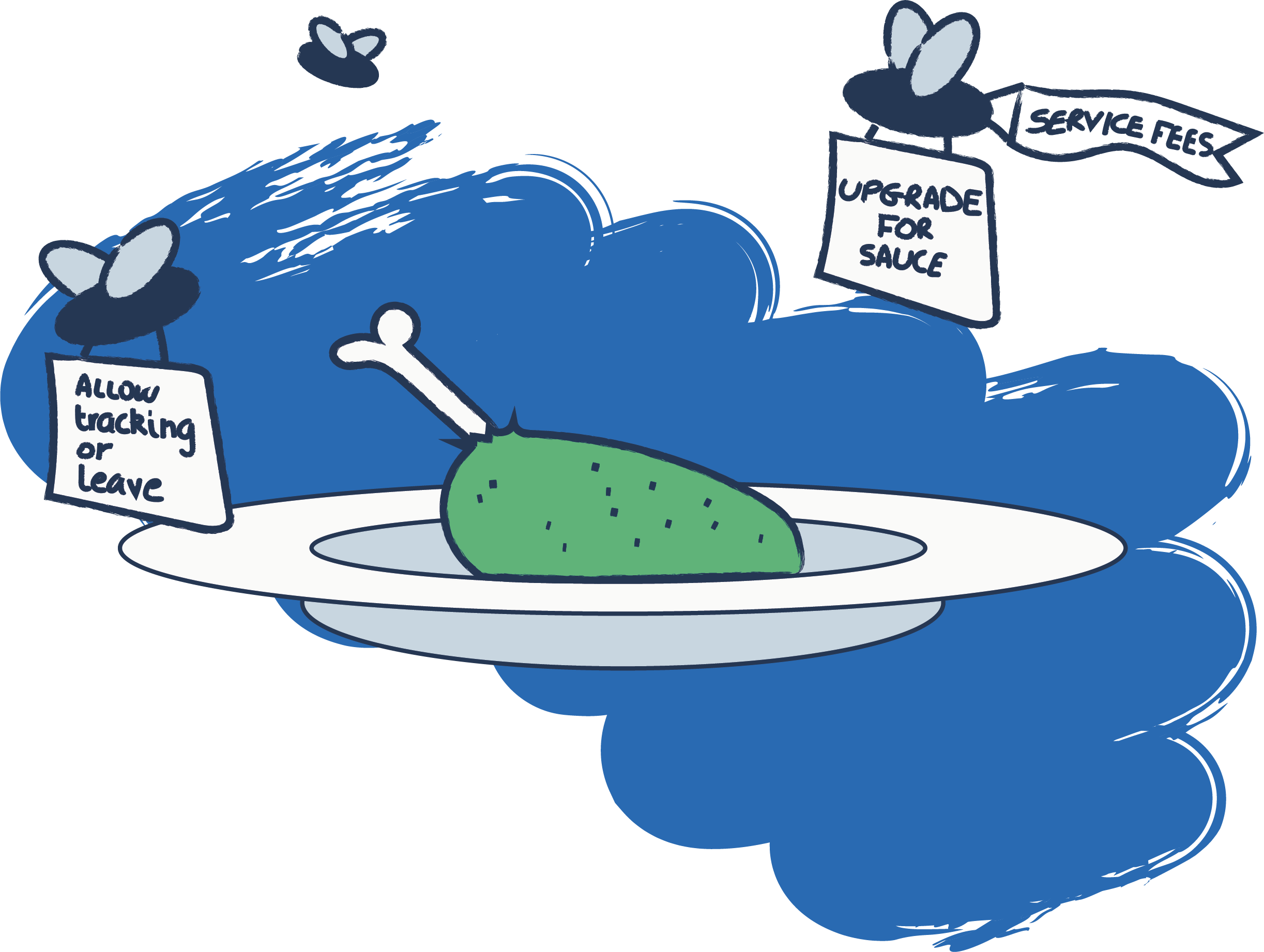

Now is the time that companies try to earn more per customer and implement monetization mechanisms. This is not in the user’s interest and is often at the expense of the user experience. Since the customers are by now switched over to their product, they can get away with a less than ideal user experience. Companies typically implement changes such as:

- Increasing the fees and costs

- Implementing monetization features, pushing the main functions to the background

- A declining service, often pushing towards a channel not preferred by the users

- Exploiting the information of the users to their own benefit

Suddenly, your Facebook feed is no longer filled with posts from your friends. Netflix removes the option to share accounts, and Adobe ensures you no longer “own” the software, but merely rent it.

While the original value of the product or platform declines, the users tolerate such changes since they can still perform the task that made them switch to the product in the first place. These changes are comparable to flies buzzing around your food; you’re still going to eat, but the process has become more annoying and less appealing.

3. Profit maximization

At last we arrive at phase 3, the profit maximization phase. This is also a phase that announces the eventual death of the product or platform. No real innovative changes are implemented, and profit is not used to invest but to pay out the managers, CEOs, shareholders, and executives.

The company focuses only on tweaking system settings to slightly boost profits, ignoring all other objectives. The business fights for a 1% improvement, but in doing so provokes the displeasure of its users. Because the company sees no huge changes in user behavior, there is no real incentive to keep up a good user experience. The real reason the users have not left (yet) is because they have not found an acceptable alternative (yet). The silent “yets” tell you what eventually will come to fruition. To quote Cory Doctorow, who wrote the in-depth essay about the phenomenon, “An enshittification strategy only succeeds if it is pursued in measured amounts. Even the most locked-in user eventually reaches a breaking point and walks away, or gets pushed.”

I can hear the familiar chorus in the background: “If you don’t pay for the product, you are the product.”

This is a common misconception. Most of us do pay for products in one way or another, yet we still end up being used and taken advantage of, often with a declining user experience. We pay for our phones, our computers, our printers, and our internet connections. We also pay for streaming services and delivery services.

But when you think about your latest experience with one of these products or services, can you honestly say they’ve improved over time? Can we truthfully claim they haven’t lured us in with a good product, only to degrade the experience later on to squeeze out more—whether through selling our data, pushing more expensive subscriptions, or adding costly extras?

To borrow a line from Cory Doctorow once again:

“If you’re not paying for the product, you’re the product, and if you are paying for the product, you’re still the product.”

How companies and designers can prevent enshittification

Product designers, UX designers, and companies should want to avoid such a death of a product or platform. Of course, in a lot of cases, the deterioration will be very slow and not as extreme as described. Yet, we would be wise to learn from companies like Facebook, Uber, Google, Twitter, etc. The answer to this decay has been half provided in the above section.

As a company, it is important:

- Find the balance between profit and an acceptable user experience. When the scales are tipped, it is hard to go back to equilibrium.

- Profit should be found not by thinning out your service(s), but by excelling in them.

- Exploit the information of the users not only for your own gain but also for theirs.

- Don’t push your monetization features, but let them exist naturally below the main functionalities, even if that means losing out on a percentage. Look out for the long run, not the quick buck.

- Change to stay, not to ignite and extinguish quickly. It all comes down to having a sustainable growth strategy.

As a designer you can:

- Actively advise against any exploitive practices and provide an experience that balances the user needs and the company goals.

- Support the company in reaching its targets; profit is not something to turn your nose up at.

- Do your research and show your company what the possible impact could be. Don’t buckle under pressure but keep an eye on the changes.

- Dare to go back in after implementation; don’t give up right away.

Ultimately, every product or service can be swapped out—your goal is to ensure your users simply never want to.